The cost of legacy SCADA systems

SCADA systems have become a common tool for advanced management and control of equipment and operations in the energy, mining, water and manufacturing sectors. Traditionally, these systems were designed around reliability and safety, and were isolated from other networks. With the advancement of technology and desire for greater transparency of operational data, this is no longer the case. Legacy systems are now becoming less able to support new safety and data processing requirements along with being at high risk of failure at any moment, so are now a major liability and the cost to asset owners can be much greater than they realise.

Installing a new SCADA system or replacing a legacy system should be viewed as an investment in efficiency, safety and operational visibility. Early in the PLC and SCADA development days, the cost of investing in hardware and software along with the design, implementation and ongoing maintenance of SCADA systems was high, this is partly the reason why many legacy systems are still operational. Another reason is the hardware was typically designed and manufactured with robustness in mind, some systems have been running for more than 20 years.

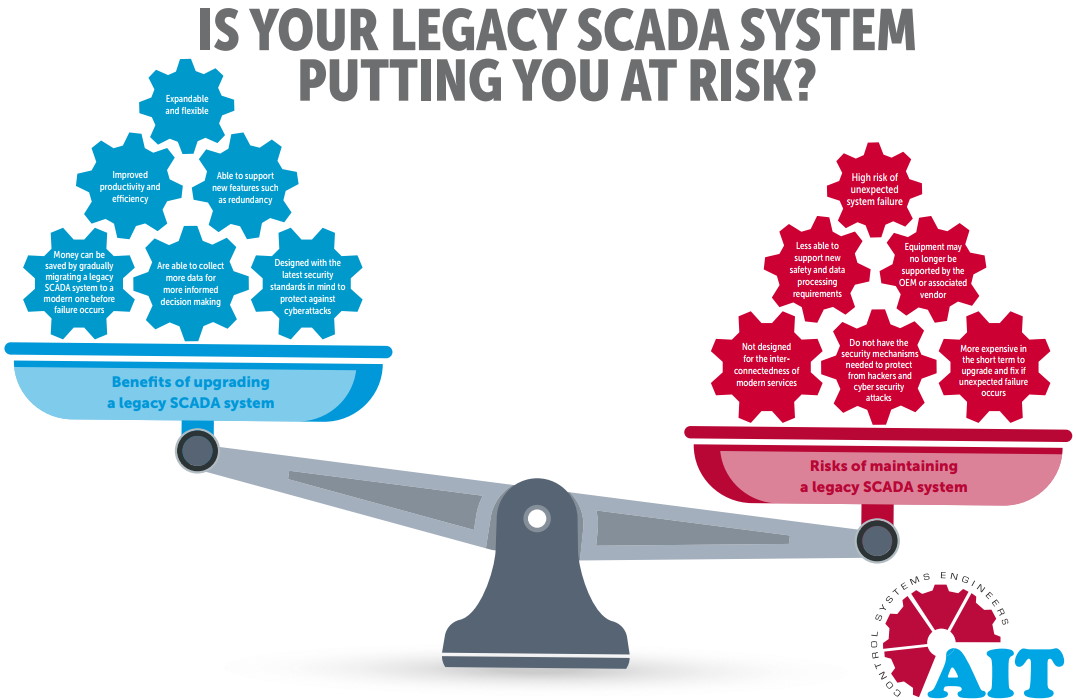

The perceived costs of upgrading a legacy SCADA system has resulted in some asset owners holding off on investing in new equipment, instead continuing to use legacy hardware and software, and adapting it to modern requirements where they can. The continued use of legacy systems has now reached the point that the benefits no longer outweigh the risks, and asset owners should be aware of the real cost of a SCADA system failure with little or no upgrade plan.

The cyber security risks

Perhaps the biggest risk of legacy SCADA systems is the threat of hackers accessing and disrupting the system, especially where critical infrastructure is involved. Many of these legacy SCADA systems were designed decades ago, back when cyber security was not a concern, however as they have become interconnected to more modern services, security has become a more prominent issue.

These legacy systems have very little implementation of standard security mechanisms, measures such as encryption is difficult to support due to lack of processing capability and legacy protocols. Authentication may not be supported, or support very low-level authentication, such as SCADA PCs sharing the same password that has been re-used for years, or in some instances, the lack of password protection at all.

Another problem linked to security is that most, if not all, legacy systems and supporting applications such as SQL servers, and network operating systems are no longer supported by the original equipment manufacturer (OEM) or associated vendor. An example being the Windows XP operating system, which has not been supported by Microsoft since 2014. We are aware of many legacy SCADA systems still running Windows XP (or even older OS versions) so this leaves them constantly open to cyberattack, not to mention the hardware itself would be well in excess of its intended design life.

The costs of maintaining a legacy system

Legacy SCADA systems and their components including PLCs, HMI, PCs, servers and networking hardware all require upgrades over time in order to keep up with latest technical developments, stay reliable, meet safety and legislative standards along with being cost effective to manage and operate.

Legacy systems are typically not supported by vendors or OEMs, this results in having to source new or second hand hardware through unsupported channels, either way the costs are generally much greater and carry many risks.

The true costs of continuing to operate a legacy system may not be immediately apparent, that is until a failure occurs, the results of which at best can be a minor disruption to a process or could result in an extended downtime period while components are attempted to be sourced, which in many cases have longer lead times and may not work as intended once installed.

Once a legacy system has been identified, some form of upgrade migration strategy should be implemented which covers not only the initial cost of the hardware, but the benefits of more robust security, improved process efficiency, greater visibility of the process, expansion capabilities, lower overall running costs and improved safety of the system.

In many cases, legacy SCADA systems can be migrated to a more modern platform over a period of time, sometimes as part of other upgrades that can occur, such as meeting the latest standards and legislation, so the total costs can be shared over time without having to spend the total amount up front.

The risk of hardware failure

Legacy systems contain aged hardware components that can fail at any time without warning. Unexpected system failures are one of the greatest risks and can also be very expensive, depending on the application and its criticality. In many cases the replacement parts are simply not available, and the upgrade is forced to occur at the worst possible time.

The cost of upgrading to the latest hardware and software needs to be weighed up against the potential costs that an unexpected system failure will incur with process disruptions that could last days, weeks or even months.

The benefits of updating SCADA systems

While it may be tempting to take an ‘if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’ mindset with legacy SCADA systems, especially when taking the perceived costs of an upgrade into account, the benefits of updating to a modern SCADA system outweighs the negatives.

New SCADA systems are much more secure against cyberattacks, they provide greater data to allow informed decisions to be made about the assets, improve productivity and efficiency, are expandable and flexible, and can incorporate new features such as redundancy if required.

To get the most out of the benefits of upgrading, it is important to consult with experienced systems integration engineering companies such as Automation IT, who are vendor neutral so can assist with all the major PLC and SCADA brands. Automation IT can assist with all levels of upgrades, from relatively simple like-for-like migration between small compatible systems, to a complete system design review and upgrade options for critical and non-critical sites that have large amounts of I/O and associated complex process control.